It sometimes seems to me as if my belly has been nothing but trouble my entire life. Up until a few years ago, nausea and vomiting were frequent occurrences for me. I felt sick so often that I gave a name – Gary – to whatever the hell it was in my belly that was causing all these problems. It’s not just Gary in there though: my fear, anxiety and depression also seem to live in my belly. Gary had a flair for the dramatic – he caused me to make many a hasty exit from polite company – but the emotions are a bit subtler. They show up as dull aches or nebulous weights in the space below my navel. In recent years, Gary seems to be largely dormant, thanks to a dramatic improvement in my diet and lifestyle. But this doesn’t mean all is peace and quiet in my belly. When I feel hurt, scared or afraid, I feel it in my belly first and most.

My belly is where I feel hunger, too, and I don’t like hunger. It took me a long time in recovery to start to learn that it is normal and healthy to feel hungry coming up to meal times and that I do not have to drop what I am doing at the first pang. I have learned to be able to sit with physical hunger and not panic. The ravenous soul-hunger of my eating disorder is a different matter. I feel that in my belly too. No wonder I over-ate so much for so long.

On top of being the site of so much inner discomfort, my belly has the cheek to

look wrong as well. I have a big fat belly, and it has, as my inner teenager puts it, Ruined Everything. I love clothes and fashion, but I have never felt free to really enjoy getting dressed because I’ve always had to compromise with my belly. Jeans and skirts have never looked right on me because the ones that fit around my belly were loose on my skinny legs. Even now, 12 stone down from my top weight, I feel I have to choose clothes to ‘camouflage’ it.

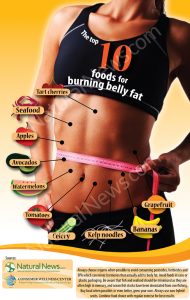

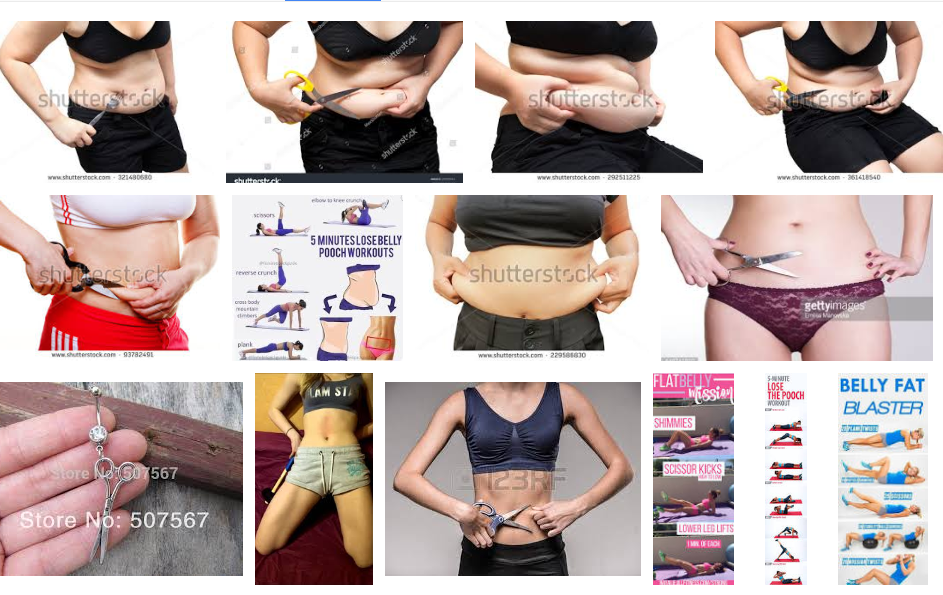

This is not some insane body dysmorphia; I did not pull this out of the air. Bellies are seen as ugly, shameful, and even frightening in our culture. Viewers of RTÉ’s recent guilty-pleasure series Frock Finders will have heard Annbury boutique’s Danny Leane repeatedly refer to the bellies of his plus-size clients as ‘the danger area’. The desire to get rid of belly fat is so common that you can get stock images of women literally cutting at their flesh with scissors, not to mention all the ads promising to reveal which foods or exercises ‘burn belly fat’.

No wonder my belly hate goes deep. Sometimes, when I can’t sleep, I pass the time by imagining what I would do if I won the lottery. Plastic surgery to get rid of my belly is almost always the first thing I think of. Not a house, not a car, not a once-in-a-lifetime holiday – no; abdominoplasty. Then, I think to myself, if I’m going to get rid of the belly, I should also get rid of the loose skin and fat on my upper arms. And, while I’m at it, I might as well get them to lift and reduce my breasts. And then there’s that loose skin under my chin and behind my knees. And the tops of my thighs are quite flabby too, and now that I think of it my ass is really disgustingly saggy… Apparently, at least on some level, my dearest wish in life is to undergo painful and potentially dangerous elective surgery in the name of beauty. And not just one surgery; once I get started, there’s no end to what I would change about myself. It’s almost like it was never really about my belly.

Susan Bordo, the brilliant feminist theorist, tells how young undergraduate women in her classes wanted to look like Kate Moss because, “She’s so detached. So above it all. She looks like she doesn’t need anything or anyone.” (“Never Just Pictures” in Twilight Zones, p. 127) The persona portrayed by the waif-like catwalk models of Moss’s era is what Bordo calls “the unfocused princess of indifference”. (“Never Just Pictures”, p. 128) Fashion has changed since the heyday of heroin chic, but the beauty ideal of our culture is still one of extreme slenderness, with a flat stomach stretched, taut and smooth, across jutting hipbones. And that ideal still represents the same detached, ethereal otherworldliness. No belly means no hunger, no fear, no needs. No demands. Bellies remind us of our own hunger. Women’s bellies in particular also remind us of pregnancy and babies, and what are babies but cuddly little balls of need?

Our whole conception of femininity centres on meeting the needs of others, especially men. As women, we are not supposed to have needs, and we are certainly not supposed to remind others – again, especially men – of any needs we might dare to have. Women’s needs are shameful in our culture. So we hide our hunger (“Oh, I’ll just have salad!”), and we hide our bellies, just like we hide our pads or tampons, so as not to upset the menfolk with the reality of our needs and our humanity. Given this context, I am full of admiration for those women who love their bellies and who enjoy them and show them off. I am not yet one of them. I can’t say I love my belly. I have only begun the task of learning to accept my belly, and loving it, like loving myself in general, is going to take work. But the work has begun, even on my belly. I may not be quite ready to show it off, but I am cross-examining my desire to cut it off. Considering where I’m coming from, both personally and culturally, that already seems like a pretty big shift.